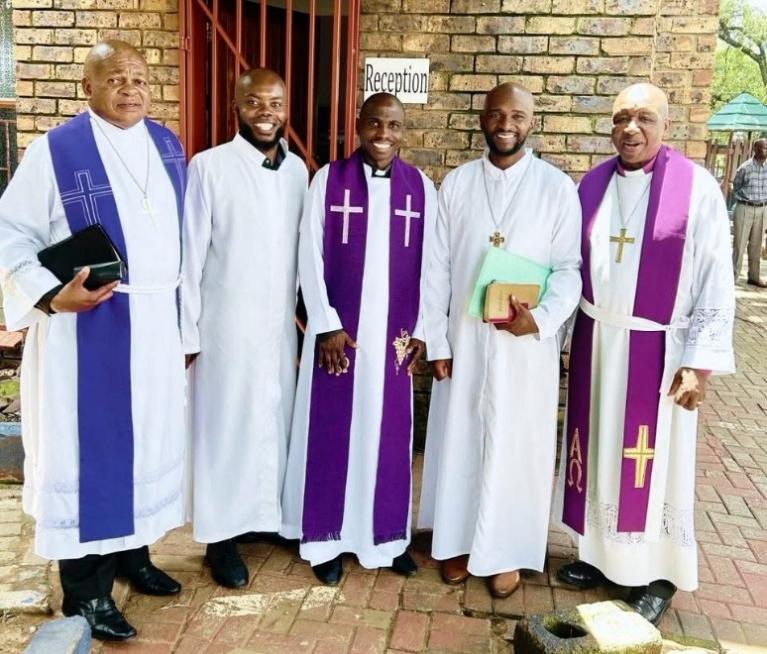

CÔTE D’IVOIRE – Rev. Marc Guehi Guehi was elected to another three-year term as National President of the Lutheran Church in Africa – Synod of Côte d’Ivoire (Église Luthérienne en Afrique-Synode de Côte d’Ivoire – ELA-SCI) on Monday, November 3, 2025.

The ELA-SCI is an observer member church of the International Lutheran Council (ILC), having been accepted into membership in 2022.

The ILC is a global association of confessional Lutheran church bodies dedicated to the proclamation of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, grounded in the authority of Scripture and the Lutheran Confessions.

———————